Refer to Figure 15-6. What Price Will the Monopolist Charge?

Chapter 9. Monopoly

9.2 How a Profit-Maximizing Monopoly Chooses Output and Cost

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you lot will be able to:

- Explain the perceived need curve for a perfect competitor and a monopoly

- Clarify a demand bend for a monopoly and decide the output that maximizes turn a profit and revenue

- Calculate marginal acquirement and marginal toll

- Explicate allocative efficiency equally information technology pertains to the efficiency of a monopoly

Consider a monopoly firm, comfortably surrounded by barriers to entry and so that it need not fear competition from other producers. How will this monopoly choose its profit-maximizing quantity of output, and what cost will it charge? Profits for the monopolist, similar any firm, will exist equal to full revenues minus total costs. The pattern of costs for the monopoly can be analyzed inside the same framework as the costs of a perfectly competitive firm—that is, by using full toll, fixed cost, variable cost, marginal cost, average cost, and average variable cost. All the same, because a monopoly faces no competition, its situation and its decision process will differ from that of a perfectly competitive firm. (The Clear it Upward feature discusses how hard it is sometimes to define "market place" in a monopoly situation.)

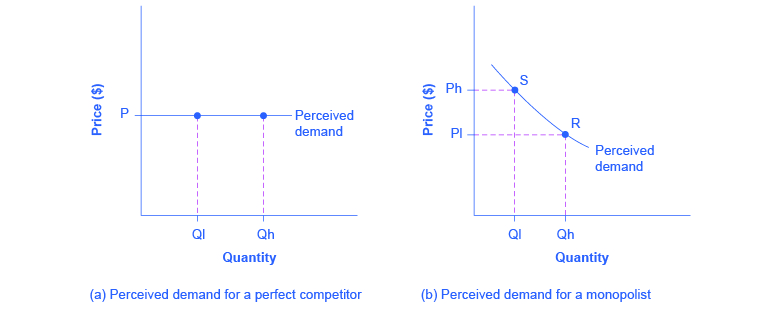

Need Curves Perceived by a Perfectly Competitive Firm and by a Monopoly

A perfectly competitive house acts as a price taker, so its calculation of total revenue is made past taking the given market price and multiplying it by the quantity of output that the firm chooses. The need bend equally it is perceived by a perfectly competitive firm appears in Figure ane (a). The flat perceived demand bend ways that, from the viewpoint of the perfectly competitive firm, information technology could sell either a relatively low quantity like Ql or a relatively high quantity like Qh at the market cost P.

What defines the market?

A monopoly is a house that sells all or nearly all of the appurtenances and services in a given market place. But what defines the "market"?

In a famous 1947 case, the federal government accused the DuPont company of having a monopoly in the cellophane market, pointing out that DuPont produced 75% of the cellophane in the U.s.a.. DuPont countered that even though information technology had a 75% market share in cellophane, it had less than a 20% share of the "flexible packaging materials," which includes all other wet-proof papers, films, and foils. In 1956, subsequently years of legal appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the broader market definition was more appropriate, and the instance against DuPont was dismissed.

Questions over how to define the market keep today. Truthful, Microsoft in the 1990s had a ascendant share of the software for computer operating systems, only in the full marketplace for all computer software and services, including everything from games to scientific programs, the Microsoft share was only near xiv% in 2014. The Greyhound omnibus company may have a near-monopoly on the market place for intercity bus transportation, just it is just a small share of the market for intercity transportation if that marketplace includes private cars, airplanes, and railroad service. DeBeers has a monopoly in diamonds, only information technology is a much smaller share of the full market place for precious gemstones and an even smaller share of the total market for jewelry. A small town in the country may have merely one gas station: is this gas station a "monopoly," or does it compete with gas stations that might be five, ten, or 50 miles away?

In general, if a firm produces a product without close substitutes, and then the business firm can exist considered a monopoly producer in a unmarried market place. Only if buyers have a range of similar—even if not identical—options available from other firms, then the house is not a monopoly. Still, arguments over whether substitutes are close or not shut can be controversial.

While a monopolist can charge whatever toll for its product, that price is nonetheless constrained by need for the firm'southward production. No monopolist, fifty-fifty ane that is thoroughly protected by loftier barriers to entry, can require consumers to purchase its product. Because the monopolist is the merely firm in the marketplace, its demand curve is the same as the market demand curve, which is, dissimilar that for a perfectly competitive house, downward-sloping.

Effigy ane illustrates this situation. The monopolist can either choose a point like R with a low price (Pl) and loftier quantity (Qh), or a bespeak similar S with a high price (Ph) and a low quantity (Ql), or some intermediate point. Setting the price likewise high will consequence in a depression quantity sold, and volition not bring in much revenue. Conversely, setting the cost too low may result in a high quantity sold, just because of the low price, it volition not bring in much revenue either. The challenge for the monopolist is to strike a profit-maximizing balance between the price it charges and the quantity that it sells. But why isn't the perfectly competitive firm's need curve besides the market place need curve? See the following Clear it Up feature for the respond to this question.

What is the difference between perceived demand and market demand?

The demand curve every bit perceived by a perfectly competitive house is not the overall market demand curve for that product. Nonetheless, the firm's demand curve every bit perceived by a monopoly is the same as the market demand curve. The reason for the difference is that each perfectly competitive house perceives the demand for its products in a market that includes many other firms; in upshot, the demand curve perceived past a perfectly competitive firm is a tiny slice of the entire market need curve. In contrast, a monopoly perceives demand for its production in a market place where the monopoly is the just producer.

Total Cost and Full Revenue for a Monopolist

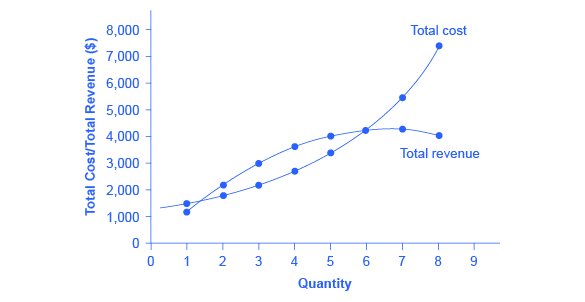

Profits for a monopolist tin be illustrated with a graph of total revenues and total costs, as shown with the example of the hypothetical HealthPill house in Figure 2. The total cost curve has its typical shape; that is, total costs rising and the curve grows steeper every bit output increases.

| Quantity | Full Cost | Quantity | Price | Total Acquirement | Profit = Total Acquirement – Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | ane,500 | i | i,200 | one,200 | –300 |

| 2 | i,800 | two | i,100 | ii,200 | 400 |

| 3 | ii,200 | 3 | 1,000 | 3,000 | 800 |

| 4 | ii,800 | 4 | 900 | 3,600 | 800 |

| v | iii,500 | 5 | 800 | 4,000 | 500 |

| half dozen | iv,200 | six | 700 | iv,200 | 0 |

| 7 | 5,600 | vii | 600 | 4,200 | –1,400 |

| eight | 7,400 | 8 | 500 | 4,000 | –3,400 |

| Tabular array 2. Total Costs and Total Revenues of HealthPill | |||||

To calculate total revenue for a monopolist, kickoff with the demand bend perceived by the monopolist. Tabular array 2 shows quantities forth the demand curve and the cost at each quantity demanded, and then calculates total acquirement past multiplying price times quantity at each level of output. (In this example, the output is given equally i, 2, 3, 4, then on, for the sake of simplicity. If you prefer a dash of greater realism, you tin imagine that these output levels and the respective prices are measured per ane,000 or ten,000 pills.) As the figure illustrates, total acquirement for a monopolist rises, flattens out, and then falls. In this example, total revenue is highest at a quantity of 6 or 7.

Clearly, the full acquirement for a monopolist is not a straight upward-sloping line, in the mode that total revenue was for a perfectly competitive house. The dissimilar total revenue pattern for a monopolist occurs because the quantity that a monopolist chooses to produce affects the market cost, which was not true for a perfectly competitive firm. If the monopolist charges a very high price, and so quantity demanded drops, and so total acquirement is very low. If the monopolist charges a very low toll, then, fifty-fifty if quantity demanded is very high, full revenue will not add upward to much. At some intermediate level, total acquirement will be highest.

Still, the monopolist is not seeking to maximize acquirement, but instead to earn the highest possible profit. Profits are calculated in the final row of the table. In the HealthPill example in Figure 2, the highest profit will occur at the quantity where total revenue is the farthest higher up total price. Of the choices given in the table, the highest profits occur at an output of iv, where profit is 800.

Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost for a Monopolist

In the existent world, a monopolist often does not accept enough information to analyze its entire total revenues or total costs curves; after all, the business firm does not know exactly what would happen if it were to modify product dramatically. But a monopolist oftentimes has fairly reliable information nearly how changing output past small or moderate amounts volition affect its marginal revenues and marginal costs, because information technology has had experience with such changes over fourth dimension and because pocket-sized changes are easier to extrapolate from current experience. A monopolist can use information on marginal acquirement and marginal price to seek out the profit-maximizing combination of quantity and toll.

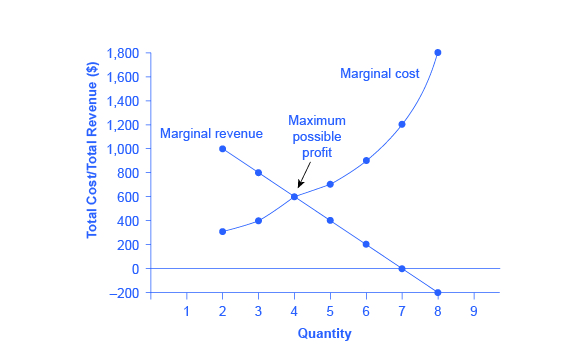

The first four columns of Table iii use the numbers on full cost from the HealthPill instance in the previous exhibit and summate marginal cost and average cost. This monopoly faces a typical upwardly-sloping marginal toll bend, as shown in Figure 3. The second 4 columns of Table 3 employ the total acquirement information from the previous exhibit and summate marginal revenue.

Notice that marginal revenue is zilch at a quantity of 7, and turns negative at quantities higher than 7. It may seem counterintuitive that marginal revenue could ever be zero or negative: after all, does an increase in quantity sold not always mean more acquirement? For a perfect competitor, each boosted unit sold brought a positive marginal acquirement, considering marginal acquirement was equal to the given market toll. Only a monopolist can sell a larger quantity and come across a turn down in total acquirement. When a monopolist increases sales by one unit, it gains some marginal revenue from selling that actress unit, but also loses some marginal acquirement considering every other unit must now be sold at a lower toll. As the quantity sold becomes higher, the driblet in price affects a greater quantity of sales, somewhen causing a situation where more than sales crusade marginal revenue to be negative.

| Cost Information | Revenue Information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Full Cost | Marginal Cost | Average Price | Quantity | Price | Total Revenue | Marginal Acquirement |

| i | i,500 | 1,500 | i,500 | 1 | one,200 | 1,200 | 1,200 |

| two | 1,800 | 300 | 900 | two | 1,100 | 2,200 | one,000 |

| 3 | 2,200 | 400 | 733 | 3 | 1,000 | 3,000 | 800 |

| iv | 2,800 | 600 | 700 | 4 | 900 | 3,600 | 600 |

| v | 3,500 | 700 | 700 | 5 | 800 | four,000 | 400 |

| 6 | 4,200 | 700 | 700 | 6 | 700 | 4,200 | 200 |

| 7 | 5,600 | 1,400 | 800 | 7 | 600 | four,200 | 0 |

| 8 | 7,400 | 1,800 | 925 | 8 | 500 | four,000 | –200 |

| Table 3. Costs and Revenues of HealthPill | |||||||

A monopolist can determine its profit-maximizing price and quantity by analyzing the marginal revenue and marginal costs of producing an extra unit. If the marginal revenue exceeds the marginal cost, and then the firm should produce the extra unit.

For example, at an output of 3 in Figure iii, marginal revenue is 800 and marginal cost is 400, so producing this unit will clearly add to overall profits. At an output of 4, marginal revenue is 600 and marginal cost is 600, and then producing this unit still means overall profits are unchanged. Notwithstanding, expanding output from 4 to v would involve a marginal revenue of 400 and a marginal cost of 700, so that fifth unit would actually reduce profits. Thus, the monopoly can tell from the marginal revenue and marginal cost that of the choices given in the tabular array, the profit-maximizing level of output is 4.

Indeed, the monopoly could seek out the turn a profit-maximizing level of output by increasing quantity by a minor amount, calculating marginal revenue and marginal toll, and then either increasing output equally long every bit marginal revenue exceeds marginal cost or reducing output if marginal cost exceeds marginal acquirement. This process works without any need to summate total revenue and full cost. Thus, a profit-maximizing monopoly should follow the dominion of producing upward to the quantity where marginal acquirement is equal to marginal price—that is, MR = MC.

Maximizing Profits

If you find it counterintuitive that producing where marginal revenue equals marginal price will maximize profits, working through the numbers volition help.

Step 1. Remember that marginal cost is defined equally the modify in full cost from producing a small amount of boosted output.

[latex]MC = \frac{change\;in\;total\;price}{change\;in\;quantity\;produced}[/latex]

Stride 2. Note that in Table three, every bit output increases from 1 to ii units, full cost increases from $1500 to $1800. Equally a result, the marginal cost of the 2nd unit volition be:

[latex]MC = \frac{\$1800\;-\;\$1500}{1}[/latex]

[latex]= \$300[/latex]

Stride 3. Remember that, similarly, marginal revenue is the change in total acquirement from selling a small amount of boosted output.

[latex]MR = \frac{change\;in\;total\;revenue}{modify\;in\;quantity\;sold}[/latex]

Step iv. Note that in Tabular array iii, as output increases from 1 to 2 units, total revenue increases from $1200 to $2200. Every bit a result, the marginal revenue of the 2d unit will be:

[latex]MR = \frac{\$2200\;-\;\$1200}{i}[/latex]

[latex]= \$thousand[/latex]

| Quantity | Marginal Revenue | Marginal Cost | Marginal Turn a profit | Total Turn a profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,200 | 1,500 | –300 | –300 |

| ii | 1,000 | 300 | 700 | 400 |

| 3 | 800 | 400 | 400 | 800 |

| four | 600 | 600 | 0 | 800 |

| 5 | 400 | 700 | –300 | 500 |

| vi | 200 | 700 | –500 | 0 |

| vii | 0 | 1,400 | –one,400 | –i,400 |

| Tabular array 4. Marginal Revenue, Marginal Cost, Marginal and Total Profit | ||||

Table 4 repeats the marginal cost and marginal acquirement data from Table iii, and adds ii more columns: Marginal profit is the profitability of each boosted unit sold. It is defined as marginal revenue minus marginal cost. Finally, total turn a profit is the sum of marginal profits. Every bit long as marginal profit is positive, producing more output will increment full profits. When marginal profit turns negative, producing more output volition decrease full profits. Total turn a profit is maximized where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In this example, maximum profit occurs at 4 units of output.

A perfectly competitive firm volition also find its turn a profit-maximizing level of output where MR = MC. The key difference with a perfectly competitive firm is that in the instance of perfect contest, marginal acquirement is equal to price (MR = P), while for a monopolist, marginal revenue is not equal to the toll, considering changes in quantity of output touch on the price.

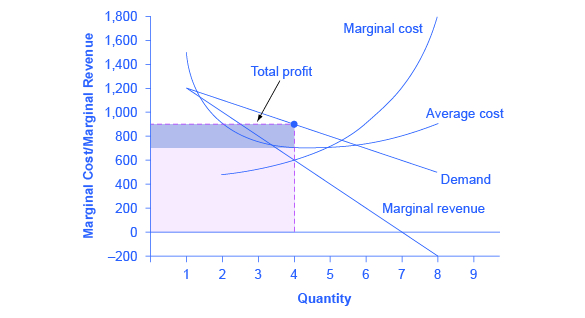

Illustrating Monopoly Profits

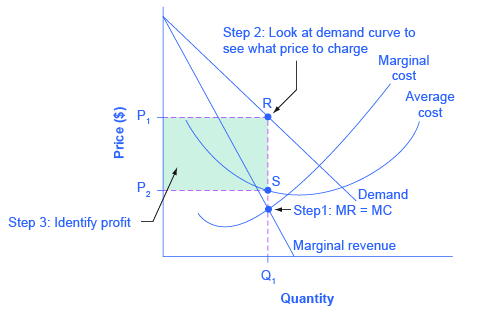

It is straightforward to calculate profits of given numbers for full acquirement and total toll. However, the size of monopoly profits can as well be illustrated graphically with Effigy iv, which takes the marginal toll and marginal acquirement curves from the previous exhibit and adds an boilerplate cost curve and the monopolist'south perceived need curve.

Effigy five illustrates the three-step process where a monopolist: selects the profit-maximizing quantity to produce; decides what price to charge; determines total revenue, total cost, and turn a profit.

Stride 1: The Monopolist Determines Its Profit-Maximizing Level of Output

The firm can use the points on the demand curve D to summate total revenue, and and so, based on total revenue, calculate its marginal revenue curve. The profit-maximizing quantity will occur where MR = MC—or at the concluding possible point before marginal costs starting time exceeding marginal acquirement. On Figure 4, MR = MC occurs at an output of 4.

Stride two: The Monopolist Decides What Price to Charge

The monopolist will charge what the market is willing to pay. A dotted line drawn direct up from the turn a profit-maximizing quantity to the demand curve shows the profit-maximizing price. This price is above the average cost bend, which shows that the house is earning profits.

Stride three: Calculate Total Revenue, Total Cost, and Profit

Total revenue is the overall shaded box, where the width of the box is the quantity beingness sold and the acme is the price. In Figure iv, the lesser role of the shaded box, which is shaded more lightly, shows total costs; that is, quantity on the horizontal axis multiplied by average cost on the vertical axis. The larger box of total revenues minus the smaller box of full costs will equal profits, which is shown by the darkly shaded box. In a perfectly competitive market, the forces of entry would erode this profit in the long run. But a monopolist is protected by barriers to entry. In fact, one telltale sign of a possible monopoly is when a house earns profits year later year, while doing more than or less the same thing, without ever seeing those profits eroded by increased competition.

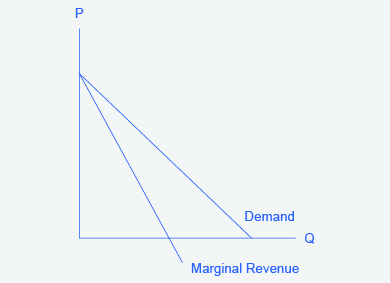

Why is a monopolist'south marginal revenue always less than the price?

The marginal revenue bend for a monopolist always lies beneath the market place demand curve. To understand why, retrieve about increasing the quantity along the demand bend by one unit, so that you have one step down the demand curve to a slightly higher quantity simply a slightly lower price. A need bend is non sequential: It is not that showtime we sell Q1 at a higher price, and then we sell Q2 at a lower price. Rather, a demand curve is conditional: If we charge the higher price, we would sell Q1. If, instead, we accuse a lower price (on all the units that we sell), we would sell Qtwo.

And so when nosotros recall near increasing the quantity sold by i unit of measurement, marginal revenue is afflicted in two means. Offset, we sell one additional unit at the new market toll. 2d, all the previous units, which could have been sold at the higher toll, now sell for less. Because of the lower price on all units sold, the marginal acquirement of selling a unit is less than the price of that unit—and the marginal revenue curve is beneath the demand curve. Tip: For a straight-line need bend, MR and demand have the same vertical intercept. Every bit output increases, marginal revenue decreases twice equally fast every bit need, then that the horizontal intercept of MR is halfway to the horizontal intercept of need. You tin see this in the Figure 6.

The Inefficiency of Monopoly

Most people criticize monopolies because they charge besides high a price, but what economists object to is that monopolies do not supply enough output to be allocatively efficient. To sympathise why a monopoly is inefficient, it is useful to compare it with the benchmark model of perfect competition.

Allocative efficiency is a social concept. Information technology refers to producing the optimal quantity of some output, the quantity where the marginal benefit to society of i more unit just equals the marginal cost. The dominion of turn a profit maximization in a earth of perfect competition was for each firm to produce the quantity of output where P = MC, where the price (P) is a measure of how much buyers value the good and the marginal cost (MC) is a measure of what marginal units toll society to produce. Post-obit this dominion assures allocative efficiency. If P > MC, then the marginal benefit to society (as measured past P) is greater than the marginal price to society of producing additional units, and a greater quantity should be produced. Merely in the case of monopoly, price is always greater than marginal cost at the profit-maximizing level of output, as can exist seen past looking back at Figure 4. Thus, consumers will suffer from a monopoly because a lower quantity will be sold in the market, at a higher price, than would have been the case in a perfectly competitive market.

The problem of inefficiency for monopolies often runs even deeper than these issues, and also involves incentives for efficiency over longer periods of time. At that place are counterbalancing incentives here. On one side, firms may strive for new inventions and new intellectual property considering they want to become monopolies and earn high profits—at least for a few years until the competition catches up. In this way, monopolies may come to be because of competitive pressures on firms. However, once a barrier to entry is in identify, a monopoly that does not need to fear competition can but produce the aforementioned old products in the same erstwhile way—while still ringing up a healthy rate of profit. John Hicks, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 1972, wrote in 1935: "The all-time of all monopoly profits is a placidity life." He did not mean the annotate in a costless way. He meant that monopolies may banking concern their profits and slack off on trying to delight their customers.

When AT&T provided all of the local and long-distance phone service in the United States, along with manufacturing nigh of the phone equipment, the payment plans and types of phones did not change much. The old joke was that you lot could have any colour phone you lot wanted, as long as information technology was black. But in 1982, AT&T was carve up up past government litigation into a number of local phone companies, a long-distance phone visitor, and a phone equipment manufacturer. An explosion of innovation followed. Services like call waiting, caller ID, three-way calling, vocalization mail service though the phone company, mobile phones, and wireless connections to the Internet all became available. A wide range of payment plans was offered, besides. Information technology was no longer true that all phones were blackness; instead, phones came in a broad diversity of shapes and colors. The end of the telephone monopoly brought lower prices, a greater quantity of services, and also a wave of innovation aimed at attracting and pleasing customers.

The Remainder is History

In the opening case, the Due east Republic of india Company and the Amalgamated States were presented as a monopoly or near monopoly provider of a skilful. Most every American schoolchild knows the effect of the 'unwelcome visit' the 'Mohawks' bestowed upon Boston Harbor's tea-bearing ships—the Boston Tea Political party. Regarding the cotton industry, nosotros besides know Bang-up United kingdom remained neutral during the Civil War, taking neither side during the conflict.

Did the monopoly nature of these business have unintended and historical consequences? Might the American Revolution have been deterred, if the Eastward India Company had sailed the tea-bearing ships dorsum to England? Might the southern states accept made different decisions had they not been and so confident "Male monarch Cotton wool" would force diplomatic recognition of the Confederate States of America? Of grade, it is not possible to definitively answer these questions; later all we cannot roll dorsum the clock and try a different scenario. We can, however, consider the monopoly nature of these businesses and the roles they played and hypothesize almost what might have occurred under different circumstances.

Perchance if in that location had been legal gratis tea trade, the colonists would have seen things differently; in that location was smuggled Dutch tea in the colonial market place. If the colonists had been able to freely purchase Dutch tea, they would have paid lower prices and avoided the taxation.

What most the cotton monopoly? With ane in five jobs in Slap-up Great britain depending on Southern cotton wool and the Confederate States nearly the sole provider of that cotton, why did Peachy United kingdom remain neutral during the Ceremonious War? At the beginning of the war, Britain simply drew downwardly massive stores of cotton. These stockpiles lasted until near the end of 1862. Why did Britain not recognize the Confederacy at that point? Two reasons: The Emancipation Proclamation and new sources of cotton. Having outlawed slavery throughout the Uk in 1833, it was politically impossible for Not bad Britain, empty cotton wool warehouses or non, to recognize, diplomatically, the Confederate States. In addition, during the two years information technology took to draw down the stockpiles, Britain expanded cotton fiber imports from India, Egypt, and Brazil.

Monopoly sellers often meet no threats to their superior market position. In these examples did the power of the monopoly blind the decision makers to other possibilities? Perhaps. Merely, as they say, the rest is history.

Key Concepts and Summary

A monopolist is non a price taker, considering when it decides what quantity to produce, it also determines the market place price. For a monopolist, full revenue is relatively low at low quantities of output, because not much is existence sold. Total revenue is too relatively depression at very loftier quantities of output, because a very loftier quantity will sell simply at a low price. Thus, total revenue for a monopolist will showtime depression, rise, and and so decline. The marginal revenue for a monopolist from selling additional units volition decline. Each additional unit sold past a monopolist will push down the overall market place price, and as more units are sold, this lower price applies to more and more units.

The monopolist will select the profit-maximizing level of output where MR = MC, and and then charge the price for that quantity of output as adamant past the market place demand bend. If that price is above average cost, the monopolist earns positive profits.

Monopolists are non productively efficient, because they do not produce at the minimum of the average cost bend. Monopolists are not allocatively efficient, because they do not produce at the quantity where P = MC. Equally a effect, monopolists produce less, at a higher average price, and charge a higher price than would a combination of firms in a perfectly competitive industry. Monopolists also may lack incentives for innovation, considering they need non fright entry.

Self-Check Questions

- Suppose need for a monopoly'southward product falls so that its profit-maximizing price is below average variable price. How much output should the firm supply? Hint: Draw the graph.

- Imagine a monopolist could charge a different price to every customer based on how much he or she were willing to pay. How would this affect monopoly profits?

Review Questions

- How is the need curve perceived by a perfectly competitive firm different from the demand curve perceived by a monopolist?

- How does the demand curve perceived past a monopolist compare with the market need curve?

- Is a monopolist a price taker? Explain briefly.

- What is the usual shape of a total revenue curve for a monopolist? Why?

- What is the usual shape of a marginal revenue curve for a monopolist? Why?

- How tin a monopolist identify the turn a profit-maximizing level of output if it knows its total acquirement and total cost curves?

- How can a monopolist identify the profit-maximizing level of output if it knows its marginal revenue and marginal costs?

- When a monopolist identifies its profit-maximizing quantity of output, how does information technology decide what toll to accuse?

- Is a monopolist allocatively efficient? Why or why not?

- How does the quantity produced and price charged by a monopolist compare to that of a perfectly competitive firm?

Disquisitional Thinking Questions

- Imagine that y'all are managing a small firm and thinking about entering the market of a monopolist. The monopolist is currently charging a high price, and you have calculated that you can make a nice profit charging ten% less than the monopolist. Earlier you lot become ahead and challenge the monopolist, what possibility should you lot consider for how the monopolist might react?

- If a monopoly house is earning profits, how much would you expect these profits to be diminished by entry in the long run?

Problems

- Draw the demand curve, marginal revenue, and marginal toll curves from Figure 4, and identify the quantity of output the monopoly wishes to supply and the price it volition accuse. Suppose need for the monopoly's product increases dramatically. Draw the new demand bend. What happens to the marginal revenue as a outcome of the increase in demand? What happens to the marginal cost curve? Identify the new profit-maximizing quantity and price. Does the answer make sense to yous?

- Draw a monopolist's demand curve, marginal acquirement, and marginal cost curves. Identify the monopolist's profit-maximizing output level. At present, think most a slightly higher level of output (say Q0 + 1). According to the graph, is in that location any consumer willing to pay more than the marginal cost of that new level of output? If so, what does this mean?

References

Aboukhadijeh, Feross. "Chapter 20: Girding for War – The Due north and the South, 1861-1865." StudyNotes, Inc. Accessed July 7, 2013. http://www.apstudynotes.org/us-history/outlines/chapter-20-girding-for-state of war-the-north-and-the-southward-1861-1865/.

British Parliament. "(28 August 1833). Slavery Abolition Act 1833; Section LXIV." Accessed July 2013. http://www.pdavis.nl/Legis_07.htm.

Dattel, E. (nd). "Cotton and the Civil War." Mississippi Historical Society. Accessed July 2013. http://mshistorynow.mdah.land.ms.us/manufactures/291/cotton wool-and-the-civil-war.

Gartner. 2015. "Gartner Says Tablet Sales Go on to Be Slow in 2015." Accessed March 12, 2015. http://world wide web.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2954317.

Grogan, David. 2015. "Federal Judge Finds AmEx's Anti-Steering Rule Violates Antitrust Law." American Booksellers Clan. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.bookweb.org/news/federal-judge-finds-amex%E2%80%99s-anti-steering-rule-violates-antitrust-law.

Massachusetts Historical Society. "The Coming of the American Revolution 1764-1776: The Boston Tea Party." Retrieved from http://world wide web.masshist.org/revolution/teaparty.php.

Massachusetts Historical Society. "Whereas our Nation." The Massachusetts Gazette, p. 2. Accessed July 2013 http://www.masshist.org/revolution/prototype-viewer.php?old=1&item_id=457&img_step=i&nmask=i&mode=large.

Pelegrin, William. 2015. "Approximate Overrules Antitrust Case Against Google , Says Setting Default Search Engines Is Off-white." Digital Trends. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/judge-tosses-out-google-antitrust-lawsuit/.

Glossary

- allocative efficiency

- producing the optimal quantity of some output; the quantity where the marginal do good to society of one more unit just equals the marginal price

- marginal turn a profit

- profit of i more than unit of output, computed as marginal revenue minus marginal cost

Solutions

Answers to Self-Bank check Questions

- If toll falls below AVC, the house will not be able to earn enough revenues even to cover its variable costs. In such a case, it volition suffer a smaller loss if it shuts down and produces no output. Past contrast, if it stayed in performance and produced the level of output where MR = MC, information technology would lose all of its fixed costs plus some variable costs. If information technology shuts downwardly, information technology only loses its fixed costs.

- This scenario is called "perfect cost discrimination." The result would exist that the monopolist would produce more output, the aforementioned amount in fact as would be produced past a perfectly competitive industry. However, there would be no consumer surplus since each buyer is paying exactly what they recall the product is worth. Therefore, the monopolist would be earning the maximum possible profits.

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/9-2-how-a-profit-maximizing-monopoly-chooses-output-and-price/

0 Response to "Refer to Figure 15-6. What Price Will the Monopolist Charge?"

Post a Comment